The Serapeum of Saqqara: A Giant Tunnel of Light?

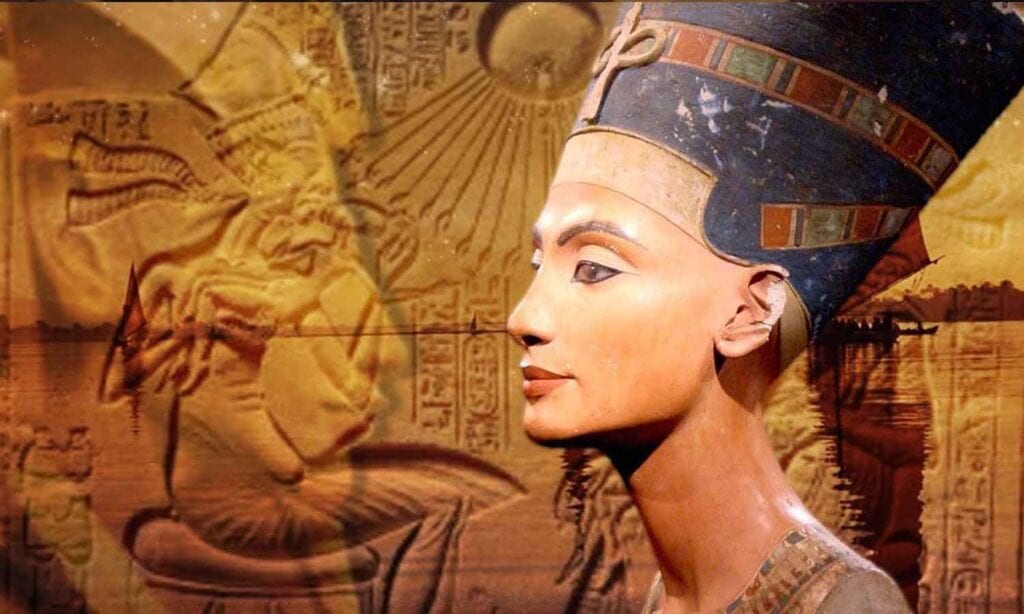

We’ll never get bored of exploring ancient Egyptian myths and legends. There’s so much history and culture there to unpack, and sometimes it feels like we’ve barely gotten started. It wasn’t until the very end of the 18th century that we discovered the Rosetta stone and began making translations of ancient Egyptians texts and hieroglyphs, and even now, much of what we believe about them is based on little more than supposition and speculation. Despite everything you were taught in school, we still don’t truly know their ethnicity. Traditionally they’re shown as being almost European in appearance, but Aristotle and Herodotus, who saw the ancient Egyptian royals with their own eyes, describe them as African.

Once you accept that the traditional picture of an ancient Egyptian is probably inaccurate, everything else starts to fall apart quite quickly. Our view of ancient Egypt and its people is cartoonish when we step back and think about it. Look at the way that mummies have been turned into little more than Halloween monsters. Pay a visit to an online slots website such as Rose Slots, and look at the way the country is presented on the games there. Online slots like ‘Crown of Egypt,’ and ‘Eye of Horus,’ might present a picturesque view of the Egypt of the past, but they’re a simple pastiche of a misunderstood culture. We don’t hold that against the people who made those online slots – they just worked with the knowledge they were taught at school. How much of that knowledge can we rely on, though? How much do we truly understand?

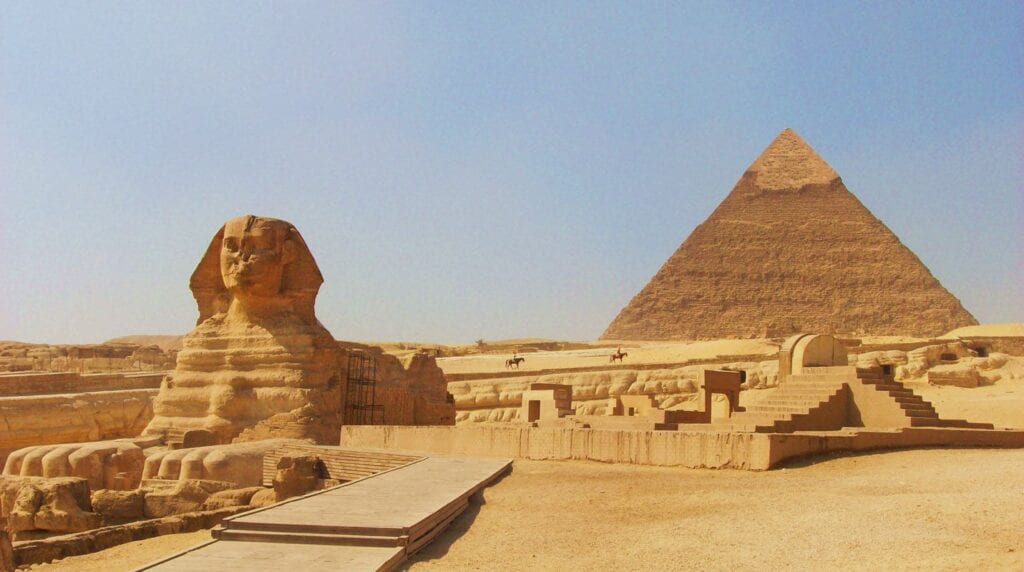

If you genuinely don’t think we’re underestimating the knowledge and the capabilities of the Ancient Egyptians, ask yourself this question. How were the pyramids built? If your answer starts with “by slaves,” we have two points to raise. The first is that you’re probably wrong because there’s a lack of any reliable evidence that slaves were involved, and secondly, “by slaves” wouldn’t satisfactorily resolve the question of how such an enormous feat of engineering was possible with so little technology. The real answer to the question is to say that we don’t know, as terrifying as that answer might be when we’ve had thousands of years to look at them. In fact, whenever an even vaguely credible theory about how they were built appears, it still makes mainstream news even today.

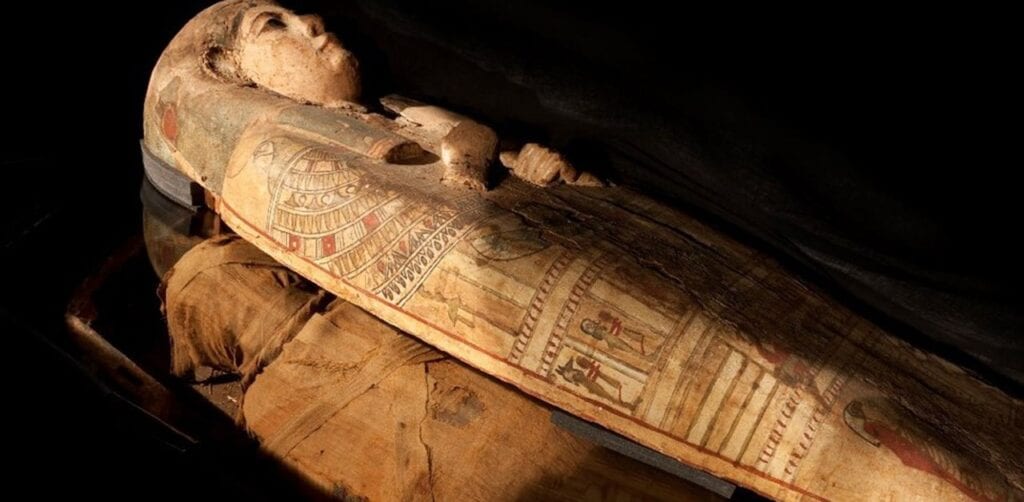

All of this leads us to the central point of our article, which is the Serapeum of Saqqara. It isn’t one of Egypt’s most famous ancient tourist attractions, but it is one of the most puzzling. Officially, the reason for this series of 24 enormous sarcophagi sat in purpose-built notches in a necropolis at Saqqara is that they’re burial tombs for Apis bulls. On the surface, it’s a fair enough assessment. Apis bulls were (we think) sacred to the people of the time, and they would have been afforded a certain amount of dignity when they passed away. Look beyond the obvious, though, and there are a lot of problems with this theory. That starts with the fact that the 24 sarcophagi are considerably bigger than Apis bulls, and much of the space inside would have been wasted if that’s all they were used for. The Egyptians didn’t make extra breathing space for their pharaohs inside their own tombs; why would they do it for bulls?

The building material is also conspicuous. The easiest material to make a large sarcophagus from in ancient Egypt – assuming that you were insisting on using stone in the first place – would be limestone. The 24 sarcophagi here hare made from granite, which is far more resistant and, therefore, far more cumbersome to work with. As a third mark against the ‘Apis bulls’ story, there’s also a distinct lack of Apis bull mummies inside the boxes. That ought to be enough to sink the established version of events, but it isn’t. Perhaps that’s because people don’t really want to consider another possibility.

In almost every other tomb in Egypt, you’ll find traces of soot on the walls and the ceilings. That’s because the workers lit torches as they labored on the monuments. Without them, they’d have been in total darkness. There is no soot in or around the Serapeum of Saqqara – and that might be because the 24 stone boxes may once have glowed with a light all of their own. Allow us to explain. Instead of assuming that the boxes were filled with dead bulls, let us instead assume they were filled with oxen, barley, beer, and bread. We know from ancient Egyptian texts that the people of five thousand years ago understood fermentation, and those are great ingredients to kickstart that process. Throw them all in the box, close the heavy lid, and allow the fermentation process to begin. As the yeast grows and thrives, increasing amounts of C02 are generated. The C02 can’t go anywhere as the granite is airtight, and the lid weighs thirty tons.

Eventually, the pressure on the granite created by the carbon dioxide will begin to affect it. Granite is made of quartz crystals. Quartz crystals, when placed under stress, generate an electrical charge. Keep increasing the pressure, and the air around the surface of the granite will begin to ionize, and if you know anything about science, you’ll know that ionization results in a glow. Various scientific experiments in the past have proved to be capable of creating glowing lights from granite under pressure. The Egyptians might have been doing the exact same thing thousands of years ago. To put it as plainly as possible, these sarcophagi might not have been sarcophagi at all. They may actually have been an artificial form of lighting that either helped workers to continue to go about their tasks under cover of darkness or keep the necropolis lit so grieving relatives and well-wishers could visit it at any time of day or night, all throughout the year.

We appreciate that this idea sounds a bit far-fetched, but it’s impossible not to think of the bigger picture when you think of the Ancient Egyptians. Until anyone can provide an adequate explanation as to how the pyramids were built, it’s perfectly reasonable to believe that they were advanced in ways that we can’t imagine today. This innovative form of lighting might be one of those ways.